Atomic Age Cinema TV 2: Atomic Boogaloo (A Critical Analysis of this Bold New Work)

Today at The Zombie Rights Campaign we are privileged to review and discuss what may be the most important film to ever critically examine the plight of the Differently Animated in American Culture: Atomic Age Cinema TV 2: Atomic Boogaloo.

A great deal more below the cut.

AAC2: EB is the second in an ongoing series of meta-filmmaking experiments from the Atomic Age Cinema team, well-known independent filmmakers and gadflies in the Bloomington, Indiana avante-garde scene, but is the first to employ its well-known Zombie star and co-founder Baron Mardi in a radical re-imagining and rejection of the entire Romero-Russo zombie movie school.

From the very beginning, AAC2 both confronts and subverts the R-R conception of Zombies, as Baron Mardi invokes the name and image of famed Romero collaborator Tom Savini in a black magic ritual to reanimate the dead, directly subsuming the Anti-Metaphysical worldview of post-Night of the Living Dead zombiism directly into the classical Voodoo zombie mythos. Boldly striking back against the empiricism and war/disease/societal decay metaphors preferred by modern American and British film creators, Mardi asserts the supremacy of the original spiritual/mystical Undead, attempting to bridge contemporary independent film with the Golden Age of Hollywood and its interpretation of the Tragic Non-Human.

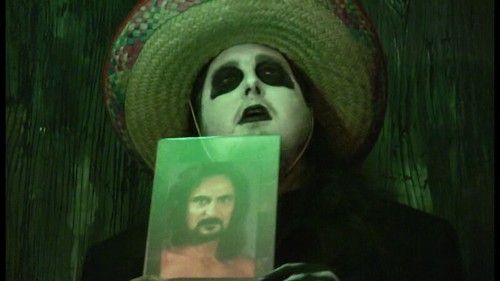

(Baron Mardi in the midst of recontextualizing the Romero-Russo-Savini Movie Paradigm)

Even more stirring from a Zombie Rights perspective is the fact that said refutation and forcible reversion of the cinematic zombie is being done by a Zombie himself, a singular figure who combines the Voodoo Priest and Zombie archetype into an entirely original form, what might be called the Fully Self-Actualized Meta-Mystical Zombie.

Aware of and attempting to transcend the inglorious history of Zombies on-screen, Mardi references and discards as unworthy of further mention the Fulci-Bava-Argento Axis of European horror, which even now finds new Unlife in its Iberian offshoots. Note carefully his use of a magical sombrero as the source of his dark magical powers; is he stating a belief in the superiority of the de Ossorio tradition, which places the Zombie within a larger pantheon of complex Undead spirits as opposed to the Fulci understanding, which places them in a Demonic or Infernal context? Perhaps it’s a sly dig at the infamously hackneyed realization of de Ossorio’s cinematic vision, which was always compromised in its execution by a lack of technical skill and directorial inventiveness? The mundane nature of the magical totem could also signify the crass and hyper-commercial nature of the modern cinematic zombie, drawing attention to the mass-produced feel of modern horror films made explicitly for, and marketed almost exclusively at the horror community.

Having staked a claim to a bold new emergent field of Zombie Film, the film turns a cold eye upon would-be reinventors of American Zombiism whose narrowness of vision confines their understanding of the Undead on Film to a post-Romero universe. AAC viciously satirizes these self-limited intellectual lightweights by sending into their midst a Voodoo Zombie, who is mistaken, in a profound and cruel act of ignorant violence for a puppet of the staid Romero hegemony.

Their cinematic gaze falls with particular harshness on Max Brooks, author of World War Z and The Zombie Survival Guide, whose work is rumored to be in development by major Hollywood players including Brad Pitt. Brooks’ labors have launched a veritable new genre of post-modern humor at the expense of the Zombie, including such recent flavors of the month as Seth Grahame-Smith; what these authors lacked in the main, however, was any appreciation of the rich history of the Zombie as icon, the Iconology of the Undead. As the modern audience lacks appreciation for, or even the memory of Zombies as committed to film and printed page in the early 20th century, the 21st century scribblers brush aside the legacy of fog-swept moonlight nights and White America’s fear of alluring yet alien African culture, instead choosing to push forward into a sterile post-racial dystopian vision, for Brooks, or a tongue-in-cheek anachronistic insertion of Zombie tropes into unrelated and thoroughly unthreatening Regency-era fiction (conveniently free of copyright restrictions and hence the need for a majority of original content) for Grahame-Smith.

AAC cuts these post-modern authors and their fans to the quick, accusing them of membership in a retrograde and insensitive culture of violence in a starkly realist climax of violence. The film seems to ask us, in haunting and memorable fashion, if our participation in Zombie Cinema is as the hypermasculine, sadistic aggressor, or if perhaps we draw some masochistic thrill at vicarious victimhood through our Undead proxies on screen. “Are you not entertained?” it boldly interrogates the viewer.

Can engagement with the Zombie on film take a cooperative, rather than parasitic and exploitative form?

(AAC2 savagely dispatches with the recent romanticization of the zombie movie fan as seen in works from Brooks, Robert Kirkman and others)

AAC2 returns to the question in the film’s second act, as the inhuman protagonists attempt to utilize their unique skills for personal enrichment through interaction with Human society. An entire discourse could be written here analyzing the threads of their restauranteur subplot, perhaps from a Marxist perspective (where it could be easily discerned that the monstrous hosts of Atomic Age represent the proletariat, thoroughly demonized by their bourgeosis taskmasters). However, that is not our purpose or mandate here at the ZRC. What matters for this discussion is that, when spurned by the elitist and self-righteous Human community, the various members of the AAC collective turn to a scheme to create a new and more tolerant community for interaction: a community of Zombies. Equally worthy of another critic’s time and attention would be the uneasy relationship between the forces of conventional religion, as embodied by Reverend Polypus, and that of Lovecraftian, cosmicism, personified by Dr. Calamari, in relation to the Zombie.

(AAC2 delves into the issue of Living-Zombie capitalistic relations in a nuanced and honest fashion)

Once again utilizing the fascinating cinematic device of the Sombrero, Baron Mardi thumbs his nose at even the venerable black and white forebears of his genre, dispensing with elaborate rituals in favor of direct action to facilitate the plot. Gone are the days, Mardi asserts, when Zombies could only be conjured into the imagination through elaborate rigamarole and suspension of disbelief; Zombies, he states, are here and now, presently realized and ready for their time at the fore of the zeitgeist.

A chilling take on the self-indulgent Zombie Apocalypse scenario follows, pointing out that, much like the Cold War concept of ‘survivor’ fiction, the entire concept is riddled with an essential self-contradiction, as the body of work simultaneously proclaims the improbability and hopelessness of survival alongside the documentation of just such improbable events, over and over on screen. What the audience gets out of the Zombie Apocalypse is not a sober rumination on the fragile nature of life, but rather, as John Varley observed decades ago regarding survivor fiction, an escapist fantasy that erases all of our personal inadequacies and gives us an ideal blank slate to recreate a world we find personally unpalatable.

(Zombie Apocalypse, or wish fulfillment of lonely nerds? AAC2 asks the hard questions)

Zombies aren’t the form of our demise, contra Romero; they’re instead used as the harbingers of a peculiar and intensely selfish form of personal salvation.

Not so fast, says the AAC crew; Zombies are merely other people, and if the Zombie apocalypse is hell, then it is only because, as Sartre observed, Hell is other people. The Zombies raised by Mardi’s character force him to hold a mirror to his own short-sightedness and reckless display of magical prowess, identifying the flaws in his moral tapestry even as they deny him personal physical refuge. Such confrontations are always difficult, if not perilous to one’s own existence. Basement Boy alludes to the struggle to vivisect one’s ego without destroying entirely the Self via an allusion to situational cannibalism; when forced face to face with the unthinkable in ourselves, can any of us say without ambiguity that we’re truly alive? After watching this scathing indictment of modern society and its relationship to the Zombie, you might want to ponder the question anew.

A final footnote: The Zombie Rights Campaign is mentioned at the close of the film in a comment by Dr. Calamari indicating that they anticipated our critical response to the film, and welcomed even a negative analysis. We are privileged to have the opportunity to perform such an analysis, and further pleased that it could be such a positive experience, for ourselves personally and for the advancement of Zombie Rights.

Update: The ZRC wishes to thank Andrew Leal, our longtime friend, ally and resource for his help in crafting this appropriately weighty review of such an important new work.

Comments